The Atlantic barrier dune ridges and N.C. Highway 12 on Pea Island, looking south towards the villages of Rodanthe, Waves and Salvo. These thin barrier islands are built, sustained and reshaped by storm surge during hurricanes and other violent storms, which wash sand across them, causing the islands to grow in thickness and elevation and migrate toward the mainland. But miles of man-made dunes that protect expensive beach homes and the sole asphalt artery threading the island villages prevent this overwash and the island-building process. Instead the islands are locked in place, and more frequent and violent storms inflamed by warming ocean temperatures threaten to wash them away. Scientists suggest that if carbon emissions continue at their current rate, the planet faces 6 feet of global sea level rise by 2100, which would inundate the Outer Banks.

The Atlantic Ocean has washed away Seagull Drive in Nags Head, and encroached upon an abandoned home that was once on the first row of homes. Others have since been demolished.

Kaine, 2, plays in the sound near sandbags installed to break waves during storms and slow erosion in the cemetery. May 2018.

The Salvo Community Cemetery in 1970, with a complete fence and a shoreline with vegetation. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Cape Hatteras National Seashore

The Salvo Community Cemetery (as seen in September 2017) after decades of erosion. The cemetery is bound by the Pamlico Sound and the Salvo Day Use Area. Both lie within the Cape Hatteras National Seashore, which is managed by the National Park Service. But the cemetery is not maintained by the Park Service, it is privately owned by the community, which was scrambling to raise the funds to save it. The next major storms threatened to wash it into the Pamlico Sound.

Research by Dr. Stanley Riggs, a professor of geology at East Carolina University, and his colleagues, suggests that the high dunes that protect the Atlantic Ocean beaches have prevented much overwash from reaching the sound side and expanding the beach a the Salvo Day Use Area. Using aerial photographs and other methods, he and a team have measured 1,500 feet of shoreline here, and concludes that from 1962 to 1998 it has eroded at an average rate of about 1 foot a year, with a high of 2.4 feet a year. Twenty years of hurricanes, and nor’easters since his study have eroded it even more. “This [cemetery] is a grand statement of how mobile this system is, how incredibly dynamic it is,” he says.

Tributes left behind on the grave of Missouri L. Midgett, who died at 10-months old in 1901.

The grave of Mary L.A. Gray, March 5, 1836 - March 7, 1902.

Jean Hooper remembers wading in the Pamlico Sound at the Salvo Day Use Area when she was a child, while her brother, Earl Whidbee, swam to a small island in Clark’s Bay, just west of the Salvo Community Cemetery. The island is gone now. She grew up in Salvo and has never lived anywhere else. The cemetery is sacred ground to her, and she wants to be buried there, right next to her grandparents, Josephine and Luther Gray, even if the Pamlico Sound eventually swallows the cemetery and she vanishes into the sea. “If I was [buried] there and the water washed me out, I wouldn't know it anyway so what difference does it make?” she says. “Might as well be there, washed out all over the place. I can't swim, but I wouldn't need to then.”

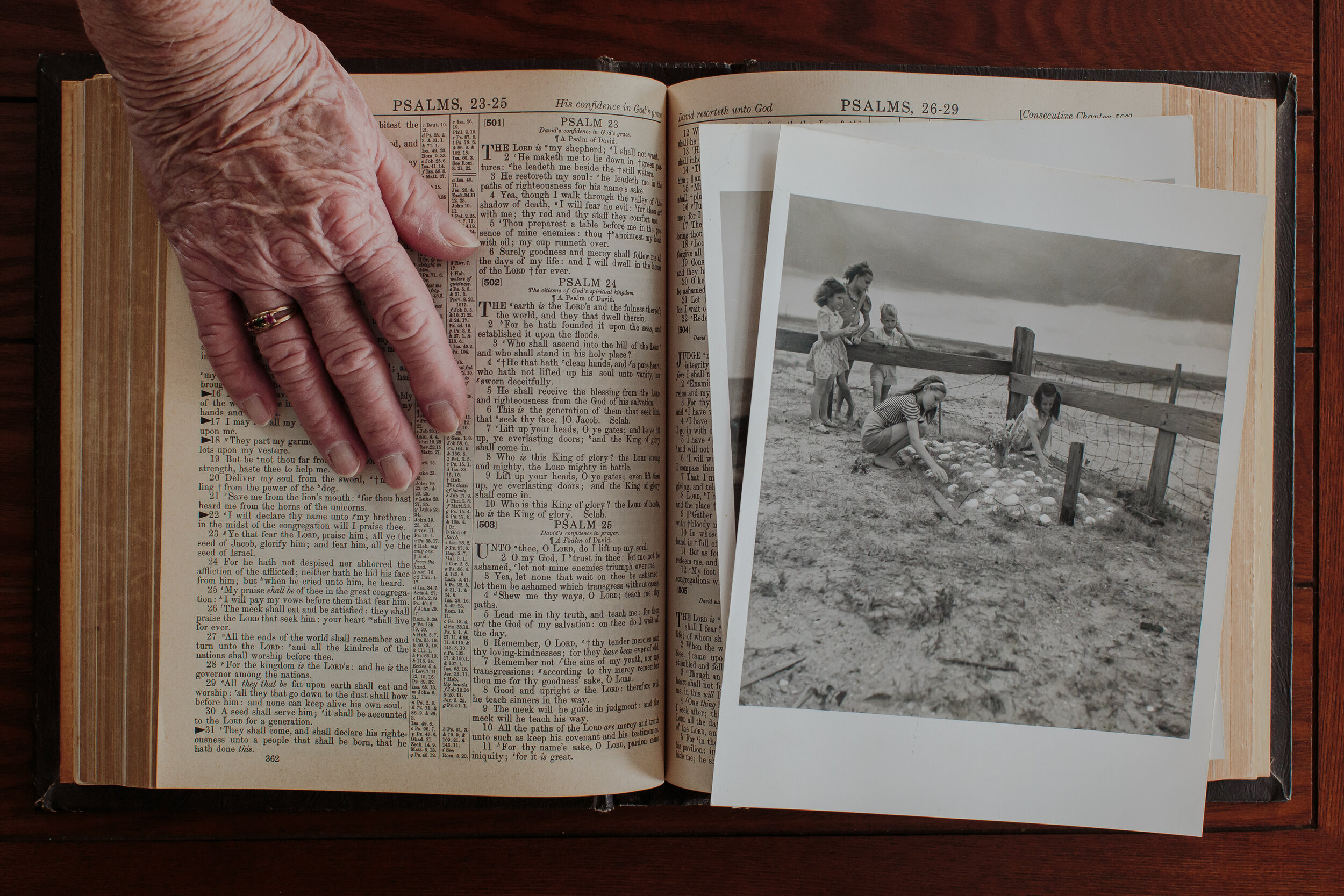

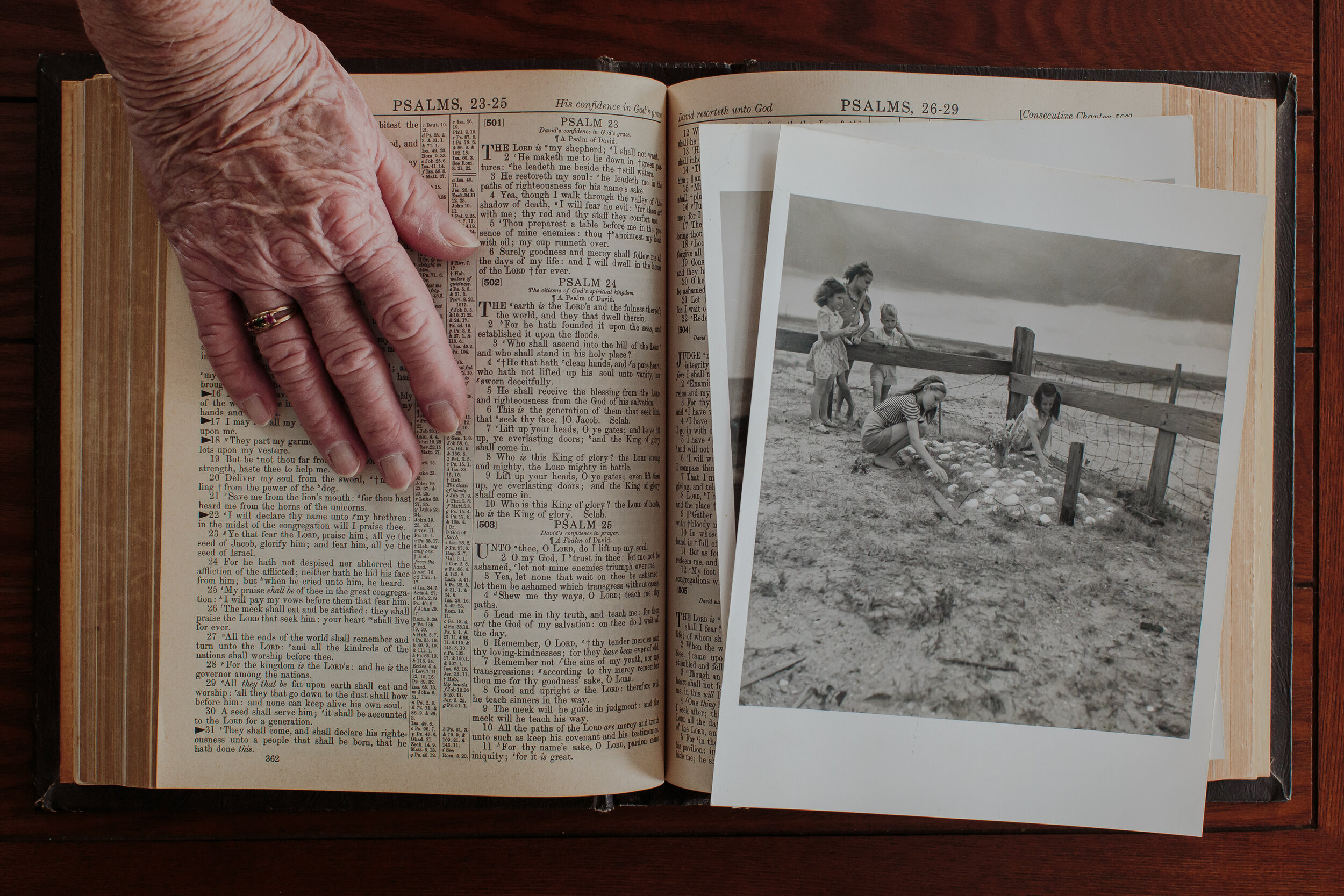

Jean Hooper has survived so many hurricanes they all blur together now, and she just accepts the storms as inevitable. Hurricane Irene in 2011 was the worst in her recent memory, and she lost most of her old photos when it flooded her house. She still has these two photos of her (far right), her sister Irene (left), and cousins (background) at their grandfather's grave at the Salvo Community Cemetery by the Pamlico Sound. They were made by Sol Libsohn, a photographer from the legendary Standard Oil Photography Project, and she’s been keeping them in her family bible ever since Irene.

Jean’s husband, Burtis, passed away in March 2019 at 85 years old, and his wife Jean had him buried in their family plot at the Salvo Community Cemetery on the edge of the Pamlico Sound, despite the fact that the site is slowly eroding into the sea. The cemetery is sacred ground to the Hoopers and many families with roots deep in the Outer Banks.

The fresh grave of Burtis Hooper, Jean Hooper’s husband, who passed away in March of 2019. He was buried right next to her grandparents, Josephine and Luther Gray.

In May 2017, tourists ran past the graves of Little Pharaoh Payne, a WWII veteran, and his wife, Hilda, which have been exhumed by storm surge. Threatened by erosion and sea level rise, the cemetery is also vulnerable to foot traffic, which wears away the sand banks. Locals get irritated when tourists don’t respect the resting place of their ancestors.

From left: Jenny Creech and Dawn Taylor both have kin buried in the Salvo Community Cemetery. They were president and vice president of the Hatteras Island Genealogical and Preservation Society, and the Rodanthe-Waves-Salvo Civic Association appointed Creech to coordinate with the community, and state and federal agencies to build a permanent bulkhead between the sound and the cemetery, which would slow erosion. Creech said that ‘solastalgia’, or a sense of loss, homesickness and distress specifically caused by environmental change around their home and a sense of powerlessness over that change was “absolutely” a driving factor in her preservation efforts. But Creech says her sense of loss is also born from the rapid unsustainable development on the Outer Banks as much as it is from the erosive effects of the sea.

David “Cowboy” Ambrose poses with his backhoe. His marine construction company is building a bulkhead that will slow erosion between the sound and the Salvo Community Cemetery. Decades ago, he fell in love with the Outer Banks and never left. “People call me cowboy because wherever I take my boots off is my home,” he says. May 2018.

The entrance to the Salvo Day Use Area and Community Cemetery. The spongey land stays flooded even after a summer thunderstorm. Sunny day flooding driven by wind and small storms is increasingly common on the Outer Banks. Today, even a strong 40-mph-wind out of the southwest on a sunny day is enough to bring the Pamlico Sound up into the cemetery.

Generations of tourists are drawn to the warm, shallow water at the Salvo Day Use Area, and many leave their mark behind on the picnic benches at the edge of the Pamlico Sound.

Katie from Michigan floats in in the Pamlico Sound.

Tourists enjoy the sunset and the newly completed bulkhead at the Salvo Community Cemetery in May 2019. Dare County won a grant for $162,000 from funds left over from Hurricane Matthew emergency relief bill. Around 6pm on summer evenings, the Salvo Day Use Area empties as the kite boarders and kayakers load up and leave for dinner. As the daylight begins to fade around 8pm, the cars show up again. Bicyclists appear and ditch their rides in the sand. If you are watching from the sound it’s as if the tourists materialize out of nothing, and scurry down to the shoreline like gazelles herding to a wet spot on a savannah. They take in the sunset through their iPhones and wade out into the sound and pose for selfies.

Large stands of wind-swept live oaks (Quercus virginiana) run parallel to the beach like tangled, twiggy cowlicks. They indicated to scientists that the land was once a ridge far from the sound — a sand pile built from Atlantic overwash and sediment delivered by two tidal creeks to the north and south. But now the tree roots dangle into the marsh. Leafless and poisoned by saltwater intrusion as the sound creeps closer, many have toppled over dead.

The eroding marsh at the Salvo Day Use Area. Winter, 2019. According to the book Rising by Elizabeth Rush, marshes are huge carbon sinks. Though coastal marshes and other wetlands only cover 5 percent of the planet’s land, they store a quarter of the carbon found in the earth’s soil, and a healthy acre of coastal marsh can clean more carbon out of the air than an acre of Amazon. When a marsh erodes and dies from saltwater intrusion, its root system will rot and releasee back into the atmosphere the gases it once sequestered, including carbon dioxide and methane, contributing to climate change.

The roots of dying marsh grass are exposed as the last remnants of marsh erode into the Pamlico Sound.

Waves slowly erode the remaining marsh at the edge of the sound at the Salvo Day Use Area.

A climate-endangered species of sandpiper known as a Willet (Tringa semipalmata) searches for prey in the balding marsh grass at the edge of the cemetery.

Periwinkle #snails in the eroding marsh grass near the cemetery at the Salvo Day Use Area.

A hermit crab made a home in a snail shell in the marsh at the Salvo Day Use Area in Salvo, North Carolina.

Laughing Gulls fly west along the Pamlico Sound.

The Milky Way stretches across the horizon over the Pamlico Sound to the west on a new moon in November 2020.

![The Pamlico Sound at the edge of the Salvo Community Cemetery is whipped up by a strong southwest wind at twilight. Rachel Carson said it best: “In its mysterious past [the sea] encompasses all the dim origins of life and receives in the end, after](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57ae023d29687fbd6a6d3b54/1598378460387-8QTP8DC001F73V2KPI7H/2019_TIDE_037.JPG)

The Pamlico Sound at the edge of the Salvo Community Cemetery is whipped up by a strong southwest wind at twilight. Rachel Carson said it best: “In its mysterious past [the sea] encompasses all the dim origins of life and receives in the end, after, it may be, many transmutations, the dead husks of that same life. For all at last return to the sea -- to Oceanus, the ocean river, like the ever-flowing stream of time, the beginning and the end." - Rachel Carson, The Sea Around Us

![The Pamlico Sound at the edge of the Salvo Community Cemetery is whipped up by a strong southwest wind at twilight. Rachel Carson said it best: “In its mysterious past [the sea] encompasses all the dim origins of life and receives in the end, after](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57ae023d29687fbd6a6d3b54/1598378460387-8QTP8DC001F73V2KPI7H/2019_TIDE_037.JPG)

The Atlantic barrier dune ridges and N.C. Highway 12 on Pea Island, looking south towards the villages of Rodanthe, Waves and Salvo. These thin barrier islands are built, sustained and reshaped by storm surge during hurricanes and other violent storms, which wash sand across them, causing the islands to grow in thickness and elevation and migrate toward the mainland. But miles of man-made dunes that protect expensive beach homes and the sole asphalt artery threading the island villages prevent this overwash and the island-building process. Instead the islands are locked in place, and more frequent and violent storms inflamed by warming ocean temperatures threaten to wash them away. Scientists suggest that if carbon emissions continue at their current rate, the planet faces 6 feet of global sea level rise by 2100, which would inundate the Outer Banks.

The Atlantic Ocean has washed away Seagull Drive in Nags Head, and encroached upon an abandoned home that was once on the first row of homes. Others have since been demolished.

Kaine, 2, plays in the sound near sandbags installed to break waves during storms and slow erosion in the cemetery. May 2018.

The Salvo Community Cemetery in 1970, with a complete fence and a shoreline with vegetation. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Cape Hatteras National Seashore

The Salvo Community Cemetery (as seen in September 2017) after decades of erosion. The cemetery is bound by the Pamlico Sound and the Salvo Day Use Area. Both lie within the Cape Hatteras National Seashore, which is managed by the National Park Service. But the cemetery is not maintained by the Park Service, it is privately owned by the community, which was scrambling to raise the funds to save it. The next major storms threatened to wash it into the Pamlico Sound.

Research by Dr. Stanley Riggs, a professor of geology at East Carolina University, and his colleagues, suggests that the high dunes that protect the Atlantic Ocean beaches have prevented much overwash from reaching the sound side and expanding the beach a the Salvo Day Use Area. Using aerial photographs and other methods, he and a team have measured 1,500 feet of shoreline here, and concludes that from 1962 to 1998 it has eroded at an average rate of about 1 foot a year, with a high of 2.4 feet a year. Twenty years of hurricanes, and nor’easters since his study have eroded it even more. “This [cemetery] is a grand statement of how mobile this system is, how incredibly dynamic it is,” he says.

Tributes left behind on the grave of Missouri L. Midgett, who died at 10-months old in 1901.

The grave of Mary L.A. Gray, March 5, 1836 - March 7, 1902.

Jean Hooper remembers wading in the Pamlico Sound at the Salvo Day Use Area when she was a child, while her brother, Earl Whidbee, swam to a small island in Clark’s Bay, just west of the Salvo Community Cemetery. The island is gone now. She grew up in Salvo and has never lived anywhere else. The cemetery is sacred ground to her, and she wants to be buried there, right next to her grandparents, Josephine and Luther Gray, even if the Pamlico Sound eventually swallows the cemetery and she vanishes into the sea. “If I was [buried] there and the water washed me out, I wouldn't know it anyway so what difference does it make?” she says. “Might as well be there, washed out all over the place. I can't swim, but I wouldn't need to then.”

Jean Hooper has survived so many hurricanes they all blur together now, and she just accepts the storms as inevitable. Hurricane Irene in 2011 was the worst in her recent memory, and she lost most of her old photos when it flooded her house. She still has these two photos of her (far right), her sister Irene (left), and cousins (background) at their grandfather's grave at the Salvo Community Cemetery by the Pamlico Sound. They were made by Sol Libsohn, a photographer from the legendary Standard Oil Photography Project, and she’s been keeping them in her family bible ever since Irene.

Jean’s husband, Burtis, passed away in March 2019 at 85 years old, and his wife Jean had him buried in their family plot at the Salvo Community Cemetery on the edge of the Pamlico Sound, despite the fact that the site is slowly eroding into the sea. The cemetery is sacred ground to the Hoopers and many families with roots deep in the Outer Banks.

The fresh grave of Burtis Hooper, Jean Hooper’s husband, who passed away in March of 2019. He was buried right next to her grandparents, Josephine and Luther Gray.

In May 2017, tourists ran past the graves of Little Pharaoh Payne, a WWII veteran, and his wife, Hilda, which have been exhumed by storm surge. Threatened by erosion and sea level rise, the cemetery is also vulnerable to foot traffic, which wears away the sand banks. Locals get irritated when tourists don’t respect the resting place of their ancestors.

From left: Jenny Creech and Dawn Taylor both have kin buried in the Salvo Community Cemetery. They were president and vice president of the Hatteras Island Genealogical and Preservation Society, and the Rodanthe-Waves-Salvo Civic Association appointed Creech to coordinate with the community, and state and federal agencies to build a permanent bulkhead between the sound and the cemetery, which would slow erosion. Creech said that ‘solastalgia’, or a sense of loss, homesickness and distress specifically caused by environmental change around their home and a sense of powerlessness over that change was “absolutely” a driving factor in her preservation efforts. But Creech says her sense of loss is also born from the rapid unsustainable development on the Outer Banks as much as it is from the erosive effects of the sea.

David “Cowboy” Ambrose poses with his backhoe. His marine construction company is building a bulkhead that will slow erosion between the sound and the Salvo Community Cemetery. Decades ago, he fell in love with the Outer Banks and never left. “People call me cowboy because wherever I take my boots off is my home,” he says. May 2018.

The entrance to the Salvo Day Use Area and Community Cemetery. The spongey land stays flooded even after a summer thunderstorm. Sunny day flooding driven by wind and small storms is increasingly common on the Outer Banks. Today, even a strong 40-mph-wind out of the southwest on a sunny day is enough to bring the Pamlico Sound up into the cemetery.

Generations of tourists are drawn to the warm, shallow water at the Salvo Day Use Area, and many leave their mark behind on the picnic benches at the edge of the Pamlico Sound.

Katie from Michigan floats in in the Pamlico Sound.

Tourists enjoy the sunset and the newly completed bulkhead at the Salvo Community Cemetery in May 2019. Dare County won a grant for $162,000 from funds left over from Hurricane Matthew emergency relief bill. Around 6pm on summer evenings, the Salvo Day Use Area empties as the kite boarders and kayakers load up and leave for dinner. As the daylight begins to fade around 8pm, the cars show up again. Bicyclists appear and ditch their rides in the sand. If you are watching from the sound it’s as if the tourists materialize out of nothing, and scurry down to the shoreline like gazelles herding to a wet spot on a savannah. They take in the sunset through their iPhones and wade out into the sound and pose for selfies.

Large stands of wind-swept live oaks (Quercus virginiana) run parallel to the beach like tangled, twiggy cowlicks. They indicated to scientists that the land was once a ridge far from the sound — a sand pile built from Atlantic overwash and sediment delivered by two tidal creeks to the north and south. But now the tree roots dangle into the marsh. Leafless and poisoned by saltwater intrusion as the sound creeps closer, many have toppled over dead.

The eroding marsh at the Salvo Day Use Area. Winter, 2019. According to the book Rising by Elizabeth Rush, marshes are huge carbon sinks. Though coastal marshes and other wetlands only cover 5 percent of the planet’s land, they store a quarter of the carbon found in the earth’s soil, and a healthy acre of coastal marsh can clean more carbon out of the air than an acre of Amazon. When a marsh erodes and dies from saltwater intrusion, its root system will rot and releasee back into the atmosphere the gases it once sequestered, including carbon dioxide and methane, contributing to climate change.

The roots of dying marsh grass are exposed as the last remnants of marsh erode into the Pamlico Sound.

Waves slowly erode the remaining marsh at the edge of the sound at the Salvo Day Use Area.

A climate-endangered species of sandpiper known as a Willet (Tringa semipalmata) searches for prey in the balding marsh grass at the edge of the cemetery.

Periwinkle #snails in the eroding marsh grass near the cemetery at the Salvo Day Use Area.

A hermit crab made a home in a snail shell in the marsh at the Salvo Day Use Area in Salvo, North Carolina.

Laughing Gulls fly west along the Pamlico Sound.

The Milky Way stretches across the horizon over the Pamlico Sound to the west on a new moon in November 2020.

The Pamlico Sound at the edge of the Salvo Community Cemetery is whipped up by a strong southwest wind at twilight. Rachel Carson said it best: “In its mysterious past [the sea] encompasses all the dim origins of life and receives in the end, after, it may be, many transmutations, the dead husks of that same life. For all at last return to the sea -- to Oceanus, the ocean river, like the ever-flowing stream of time, the beginning and the end." - Rachel Carson, The Sea Around Us